Robert Henri’s Exceptional Contribution to American Realism: The Cases of ‘Dutch Joe’ and ‘Willie Gee’

By Scarlett Ryder, Third Year History of Art

Robert Henri is widely considered as one of America’s most influential artists – through his stunning portrayals of life in New York City, and as a pioneer of the Ashcan School of American realism. In this piece, The Bristorian explores the significance of two of his most charming portraits, that of Dutch Joe (1910) and his Portrait of Willie Gee (1904).

When one thinks of the Ashcan artists, words like dynamic, sensitive, and unprecedented come to mind, yet Henri’s Dutch Joe and Portrait of Willie Gee possess a subtlety that eclipses conventional Ashcan work. On the face of it, the two paintings are very similar in medium, date and subject matter, but these two children represent distinct opposites.

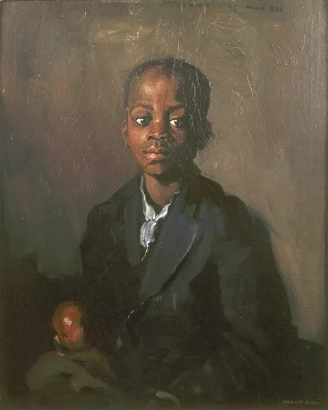

Portrait of Willie Gee (1904) (left) and Dutch Joe (1910) (right). No copyright infringement intended.

There is a false simplicity which seems to govern both paintings; both boys are the sole subjects, but it is in their expressions where Henri gives away his own feelings about the two children.

Despite the similarity of their ages, Dutch Joe is presented as strikingly more childlike than Willie Gee. This can principally be attributed to Joe’s complexion, in which he has very pink cheeks, that I would speculate are a result of him playing outside. Through this, Henri captures Joe’s youthful innocence, portrayed also by his particularly toothy grin in the centre of the composition.

His angular front teeth are puzzlingly akin to those of a rabbit, conveying the same naivety depicted in his coloured cheeks. His buckteeth are sandwiched by a strong red lip - the most vibrant colour in the portrait, which in turn draws attention to his mouth. Perhaps this is Henri’s way of showcasing children’s ability to converse respectfully with adults.

Joe’s mouth is on the one hand a physical characteristic, but arguably Henri puts it at the centre of the composition as a comment on verbal immaturity. Dutch Joe does not adhere to the traditional notion that children should be seen and not heard, in stark contrast to the example of Willie Gee.

Henri’s Portrait of Willie Gee is a remarkable representation of a young black boy in New York, particularly in consideration of the timeframe. The total respect in which the artist depicts Willie Gee is an astounding example of Ashcan authenticity, particularly through its emphasis on the young boy’s individuality.

Willie Gee’s demeanour is one of calm and self-assurance; his eyes evade the spectator - he is aware of our presence. He looks to his left, but not to anything, rather, he is in a state of reflection that is far beyond his years.

His features are soft and symmetrical, unlike those of Dutch Joe. Rather than emphasising his mouth, Henri highlights his bold eyes with white paint; the difference between Willie Gee and Dutch Joe is that Willie Gee is an observer, a contemplator.

Henri has taken great care to create a linear portrait, drawing attention to the subject matter above painterly skills. This is in stark contrast to Dutch Joe, where the brushstrokes are messy, emphasising the artificiality of the portrait itself, a reflection of Dutch Joe’s more excitable personality.

Considering that Henri painted these portraits in the first decade of the 20th Century, his disregard for contemporary racial attitudes is quite astounding. Willie Gee was painted just eight years after the Supreme Court’s landmark ruling Plessy v. Ferguson in which segregation (and the term ‘separate but equal’) was upheld in American law.

Willie Gee himself was the son of two former slaves who had moved from Virginia to New York in search of greater opportunities.[1] Henri moved to New York the same year as he painted Willie Gee, who used to deliver his papers in the morning, showing how much of an impression the child made on Henri.

American art historian Rebecca Zurier, in her fantastically written book Picturing the City, makes a point that I think demonstrates just how progressive Henri was. She comments that ‘whatever Henri’s intention in executing the portrait, it is an implicit rebuke to the white American painters who depicted blacks in a racist manner’.[2] I would highly recommend Zurier’s book as a highly informative guide to Ashcan art.

Furthermore, art critic Rose Henderson has pertinently pointed out that Henri’s own background, including having family in Virginia and ancestors from Europe, may have shaped his contemporarily liberal values.[3]

Henri had little interest in depicting the rich and vain, but rather the various realities of people who existed in what was becoming a metropolitan hub of the world in New York. For that he must be given considerable praise.

Henri’s passion for art was translated into his extensive career as a teacher in which he was single minded in wanting to inspire the next generation of artists. It would be correct to assume that through both his portraits he displays an understanding of young people that perhaps would not have been so obvious with men of his own generation.

Though I have outlined some major differences between Dutch Joe and Portrait of Willie Gee, I would like to also emphasise their similarities. Both boys have an innocence to them which Henri uses to convey a social message: that they are children that have been thrust into adult life because of great social difficulties.

They are in some ways timeless depictions, but I think it would do Henri’s work a great disservice to not contextualise them. The turn of the 20th Century was one of the most transitional moments the world has ever seen. Dutch Joe and particularly Willie Gee are, therefore, much more than portraits of children; they are symbols of the new modern world.

To conclude, Robert Henri is a fascinating artist who was able to capture the very essence of real people no matter who they were. His own words sum up his outstanding contribution to art and wider society.

‘I have but one intention and that is to make my language as clear and simple and sincere as is humanly possible … All my life I have refused to be for or against parties, for or against nations, for or against people. I do not go from land to land to contrast civilisations.

I seek wherever I go only for symbols of greatness, and as I have already said, they may be found in the eyes of a child, in the movement of a gladiator, in the heart of a gypsy, in twilight in Ireland, or in the moonrise over the desert.’[4]

Footnotes

[1] Robert Slayton, Beauty in the City (2017), p.154

[2] Rebecca Zurier, Picturing the City (2006), p. 129.

[3] Rose Henderson, Robert Henri (American Magazine of Art, 1930), p. 4.

[4] Robert Henri, Cited in: Henderson, Robert Henri, 1930, p. 8.

Image Credits

https://www.artsy.net/artwork/robert-henri-portrait-of-willie-gee

http://www.artchive.com/artchive/H/henri/henri_joe.jpg.html