Chartism and the Newport Rising: Was it Worth the Sacrifice?

By Mollie McLaughlin, First Year History

Chartism emerged as one of the defining political movements of the 19th Century. Its intense lobby for political representation is a fascinating story, and one of its chapters is the tragic tale of the Newport Rising, where state repression claimed the lives of at least 22 Chartists. In this piece, The Bristorian reflects on the Chartist movement, asking whether their strife ended with the tangible change they desired.

Chartism was one of the great revolutionary movements, catalysed by economic and social change (or lack thereof) during nineteenth century Britain. In part due to the limitations of the 1832 Great Reform Act, Chartism emerged as a large-scale political movement among the middle and working classes that used charters to lobby for constitutional change.

Historians have argued over the origins of Chartism. Some see it as a product of the economic instability stemming from the post-war depressions that dominated the period following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. While others argue its political programme captured the feeling of increasing social dissatisfaction with the lack of progressive reform; the Factory Act of 1833; the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834; and of course, the Reform Act of 1832.

Either way, the People’s Charter, named after the Magna Carta and inspired by Paine’s Rights of Man (1791), was devised in 1838 by William Lovett and Francis Place of the London Working Men's Association (LWMA) to state and petition their case. In it they had six clear aims:

The six points of the People’s Charter:

1. Universal male suffrage (the right to vote for all men over 21)

2. Voting to take place by secret ballot

3. Annual parliaments, rather than every 5 years

4. Constituencies of equal size

5. Payment for MPs

6. The abolition of property qualifications to vote

The emergence of Chartism in the 1830s and 40s was seen as a revolutionary awakening across Britain. Its influence spread quickly throughout the industrial villages and towns of Northern England, such as Bradford and Stockport. But it also prompted significant engagement from rural areas across the South Wales valleys, the Black Country, and parts of the West Country. Instrumental in its proliferation was Feargus O’Connor, a prominent radical leader and owner of the Chartist-backed newspaper The Northern Star.

The movement demonstrated many significant developments throughout the course of its campaign, with activity peaking in 1838-40, 1842 and 1848, emphasising sites of working-class discontent over Whig reforms. It offered a shared impetus for radicals and reformists to get behind since Britain’s electorate represented only 5% of its population, a symbol of Whig reticence under Earl Grey’s government.

The Chartists’ rapid increase of support soon led to the National Convention of 1839, where their first petition was presented to Parliament and unsurprisingly, was rejected, despite 1.25 million signatures from both men and women advocators.

Tensions soon arose from the lack of support from Parliament and from the threat of an armed rising started to sweep across Britain. In the autumn, meetings were convened to organise a national protest, but only one came to fruition in South Wales: The Newport Rising of 1839.

Wales was no stranger to radicalism and protest during the nineteenth century. The Merthyr Rising of 1831 saw a long week of revolt over low wages, unemployment, and the need for reform; the Scotch Cattle (striking coal miners) engaged in a terror of the Valleys during the 1820s, while the Rebecca Riots saw protests against increasing levels of taxation and tollgates in the agricultural sector between 1839 and 1843. Thus, Welsh revolutionary fervour was plentiful as the Chartist movement started to take hold.

As November contains the 182nd anniversary of the Newport Rising, why exactly is it important and why did members of the working class give their lives for the right to vote?

On the 4th of November 1839, 7,000 colliers and ironworkers led by John Frost, Zephaniah Williams, and William Jones, marched through the South Wales Valleys to Newport, advocating for the release of prominent Welsh Chartist Henry Vincent. Vincent was sentenced to a year of imprisonment after being convicted of seditious libel and conspiracy, leading to further political turmoil among Welsh Chartists. Wales and indeed Britain almost had its Bastille moment.

Several Chartists had already been arrested during the march and were held at the Westgate Hotel. Yet what was a peaceful protest soon turned into a bloody battle when troops waiting for the marchers opened fire as they arrived at Westgate Hotel in central Newport. Despite the soldiers being outnumbered by thousands of angry protestors, their armed advantage resulted in the killing of 22 Chartists, with 50 injured (more than half of the number killed in the Peterloo Massacre of 1819), and ultimately led to another failure for Chartism.

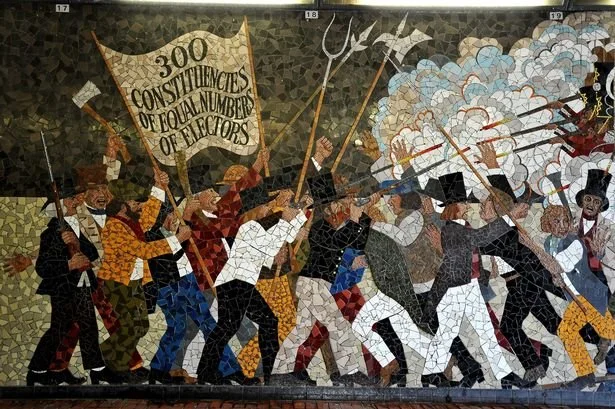

A mural of the Newport Rising, controversially removed by the Newport Council in 2013.

Between 100-200 Chartists were arrested following the riots and in January 1840, the three leaders were charged with treason and sentenced to death. However, their sentences were later reduced to transportation to Australia.

The South Wales Chartists were not only notorious for their efforts during the Newport Rising, but they were ahead of their time, with their ambitious goal to establish a People's Republic in the South Wales Valleys. They highlighted the long-awaited need for change and were role models for Chartists across Britain.

The Newport Rising, however, was not the last of Chartist radicalism. Support peaked during the economic depressions in 1839-42 and 1846-48, resulting in riots in Stockport and Manchester; and the Plug Plot of 1842 saw strikes in Yorkshire, Lancashire, the Midlands, and parts of northern Scotland, involving up to half a million workers. Chartists very much continued with their campaign.

The movement also saw more national petitions pushing for the 6 points and the transformation of the political system. The petitions presented were rejected by both Peel’s Tory government in 1842 and Russell’s Whig government in 1848, despite the 1848 version accumulating some 6 million signatures.

Consequently, due to repeated failure and divisions within the Chartists themselves, the movement declined and throughout the 1850s it was clear that equal parliamentary representation and democracy was not achievable in the short term.

Today, in a society where men and women of all social classes have the right to vote, the memory of the Chartists lives on, and its legacy is commemorated across Britain. By 1918, all Chartist demands had been achieved (apart from annual parliaments) and the Representation of the People Act finally gave working-class men the right to vote (and some women!).

It is not possible, however, to discuss the importance of Chartism without mentioning the Newport Rising. Not only is it one of the most memorable events in the history of Chartism, but it stands as the last mass armed rebellion in Great Britain, marking it as a significant event within working-class history.

Ultimately, the Chartist movement petered out before any of its fundamental aims were achieved. Yet its values were carried into the 20th Century, where its aims were finally realised. So, was it worth their sacrifice?