Making Ireland Pay: Extracting Revenue from England’s First Colony in the Middle Ages

Prof. Brendan Smith, Professor of Medieval History

Prof. Brendan Smith contributes his research that looks into the Irish exchequer reports to understand the English colonial hold of Ireland during the Middle Ages and those who lived and worked in medieval Ireland.

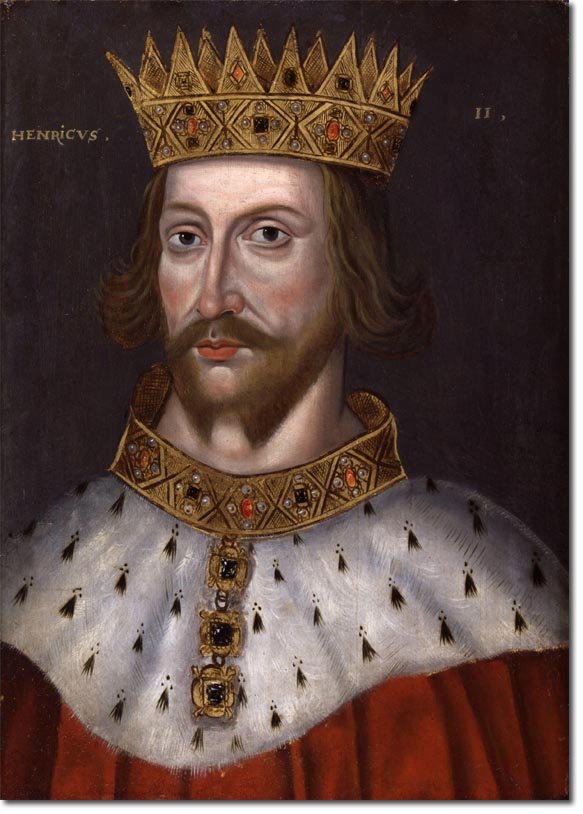

In 1171, King Henry II travelled with an army to Ireland and added the island to his domains. From the outset, the English conquest was accompanied by English colonisation – the king granted huge estates in Ireland to his favourite lords, and they imported peasants and townsfolk to stock their new acquisitions. The colonial character of the enterprise was to be seen in the landscape, where the English system of agricultural exploitation – manorialism - was imposed and scores of new towns established. Many of these huddled close to the newly built stone castles, which were themselves a powerful statement of the imposition of a new political order. The colonial reality was also proclaimed in the legal status of the colonists. They remained subjects of the English king, and while they might never set foot in England again, they continued to have access to English common law. The majority Irish population among whom they lived did not enjoy this right, despite also theoretically being subjects of the king.

When Henry II embarked on his Irish expedition, he took with him not only troops and horses, but also vast quantities of wax. This was to be used not only to provide light but also to seal the many charters that the king would issue in his new possession. The conquest of Ireland was a spectacular episode of bureaucratic colonisation. To guarantee the continued access of the colonists to English law, a replica of the English legal system with its courts and judicial offices had to be transplanted across the Irish Sea. This system was inseparable from the pattern of local government that prevailed in England, and so it was necessary that in Ireland also, shires or counties be established. At the head of the county, the administrative structure was the sheriff (shire reeve) who represented the crown in the locality. In this role, the sheriff fulfilled a range of important functions – he acted as judge in the county court; he was a military commander of the local levies in times of war; he collected the sums owed to the king in the area under his authority.

It was expected that the conquest of Ireland would add to the wealth of England and its king. English coinage flooded into the country and was soon minted there as well, allowing the profits derived from the exploitation of Irish land and from the operation of the legal system to be converted easily into hard cash. Along with its judicial arm, the two great offices of royal government in England were the chancery – the letter-writing office – and the exchequer, which coordinated the collection and disbursement of royal revenues. Within a generation of Henry II’s conquest, Ireland had its own chancery and exchequer, modelled on the English pattern and staffed by civil servants sent from Westminster.

Most of the original records produced by the Irish judicial benches and chancery in the Middle Ages have been lost, though copies of some of this material made in later periods can be used to partially reconstruct them. Medieval Irish exchequer records have fared better, with an almost complete series of documents produced in Dublin between the late thirteenth and early fifteenth centuries available for consultation in their original form. These records are kept at The National Archives, Kew. They came to be part of the English state archive as a consequence of the corrupt practices of the Irish exchequer. From 1293 onwards, the Irish treasurer – the head of the exchequer – was required to bring copies of his accounts to Westminster on an annual basis to have them audited by his English equivalent. These copies remained in London when the Irish treasurer returned to Dublin. This proved very fortunate for modern historians since in 1922, at the start of the Irish Civil War, the original manuscripts were lost in the explosions and fire that destroyed the Public Record Office of Ireland and other parts of the Four Courts complex on the north bank of the Liffey.

The records of the medieval exchequer present in remarkable detail the realities of life in colonial Ireland. The receipt rolls, for instance, record on a daily basis the sums of money handed in at the exchequer, who brought these sums to Dublin, and what demand of the crown they were intended to meet. They thus reveal the names of the various sheriffs in the counties of Ireland and how often they travelled to the exchequer, as well as how much money they carried on each of their visits. They also let us see what percentage of crown income was made up of the profits of the judicial system, how much came from the customs payments demanded from the coastal towns and the size of the contribution of rent paid by individuals holding lands and offices in Ireland of the crown. The receipt rolls can be read alongside the issue rolls, on which were recorded the payments from the exchequer authorised by the crown as it exercised its power on the island. Entries on the issue rolls identify the salaries paid to government officials, the sums allocated to maintain government properties such as royal castles, and the amounts handed over to reluctant farmers whose produce was subject to compulsory purchase to feed the king’s armies.

Read in conjunction with each other over a period of more than a century, and the exchequer records present a vivid picture of the waning fortunes of English rule in medieval Ireland. At the beginning of the period, in the late thirteenth century, the Irish colony contributed modest amounts to the English exchequer; by the 1440s, it depended for its survival on subsidies from across the Irish Sea.