“For Your Convenience”: The Queer Geographies of the Dark

via Unsplash

By Lewis Goode, Third-Year History

For LGBTQ+ History Month, Lewis explores the ways in which nighttime public spaces allowed for homosexuality to flourish prior to legalisation in the UK

The nighttime has historically been a place in which queer people are able to express themselves. Their acts and identities confined to the hours of darkness where there are fewer people to oppress their identities and acts. While not all queer identities were confined to the darkness, many found solitude and escape from the all-seeing daylight gaze, or via street lamps. Places, such as public toilets, parks, and darkened streets allowed for queer sexual encounters to take place.

In order to understand this phenomenon further we must tackle some important concepts, such as the significance of the night and the urban space. These two factors have significance in understanding the reasons why these activities could only happen at night, or out of sight, and, why they primarily occurred in cities.

Tim Edensor states that even though widespread illumination has banished darkness in most spaces in the city, it is impossible to fully illuminate a city. [1] Consequently, darkened corners and spaces are formed in which illicit and hidden activities could occur outside of the gaze of the light and the authorities.

Furthermore, understanding the importance of the metropolis to queer identities provides further significance to the study of spaces used by homosexual men. Urban spaces, compared to the sparsely populated rural spaces, allowed homosexual men to encounter like-minded people and create spaces dedicated to sexual exploration. Mark Houlbroune reveals how there is a strong link between queer identities and urban spaces in his study of queer experiences in London: "Cryil L., who moved to London in 1932 stated that he has ‘only been queer since I came to London… before then I knew nothing about it.’ [2]

Public parks, toilets, and dark streets all became viable spaces during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in which homosexual men could engage in same-sex relationships, expressing sexual desires and identities. One of the ways in which this could occur was through the practice of cottaging. Cottaging, also known as cruising, is the act of engaging in sexual acts (predominately homosexual) in public toilets.

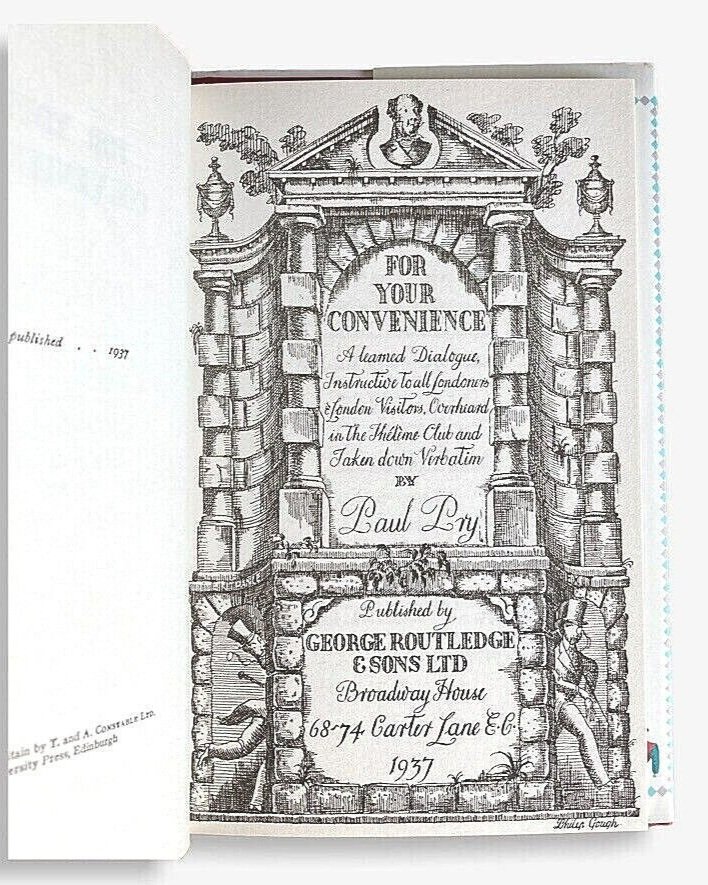

A guide published in 1937 for gay men entitled ‘For Your Convenience’ detailed the best toilets for cottaging. While being sexually implicit, discussing toilets for gentlemen to find ‘relief,’ the book detailed the pleasures and perils of most toilets around London. Away from the eyes of the public, like-minded men were able to interact within these secluded and private spaces.

Extract from ‘For Your Convenience’, published in 1937

While ‘For Your Convenience’ provides historians with the geography of homosexual acts in London, the frequent use of innuendo means that the acts committed within these spaces are left unrecorded – as with most historical accounts of sexual activities. Therefore, historians are left to rely on police reports which detail the acts committed. These reports, prior to the legalisation of homosexuality in 1967, are consequently hostile towards those convicted. Even then, the hostile tone of the language and authoritative nature of police reports means that historians are still left to assume which acts were being committed.

Another significant space in which men could seek like-minded people were parks. Parks, in their nature, provide large dark spaces with cover as they were unilluminated by street lights, providing bushes and shrubs as cover. The Times in 1843 detailed a police report convicting two men of ‘indecently exposing themselves’ to each other in Hyde Park. While parks were also used for sexual activities by other groups, the large parks located in London offered large oases of darkness to conduct these queer sex acts.

Upon the beginning of the Second World War, we see the darkness of the blackout being used in a similar way. Here darkness was not confined to certain locations as the whole city was plunged into darkness. The lack of visibility, combined with the increased number of people in cities and in Britain, meant that more queer encounters occurred.

Emma Vickers conducted interviews with queer veterans who served in the armed forces during the Second World War. One testimonial described how a senior sergeant used the jolting of a truck (or the apparent jolting) to make ‘explicit sexual manoeuvres’ on the interviewee – the blackout enabled for no one to see this take place.[3] Another interviewee, Jimmy Jacques, stated how he had sex ‘believe it or not, in the (army) showers’ with a physical training instructor. [4]

In demonstrating that homosexuality in the armed forces existed in large numbers, Vickers also explores the geographies in which soldiers were able to encounter like-minded people. These spaces transgressed notions of public and private spaces and create unique geographies in which queer encounters could occur. Enabled by darkness or privacy, public spaces were transformed into spaces where queer cultures and identities could thrive.

By looking at these spaces we can see how homosexual men have used dark and private spaces to express themselves and have sexual encounters with like-minded people. These spaces helped to build up networks of queerness in varied metropolitan areas that were accessible to all. While the sexual identities and motivations of these people may be unclear and may never be fully understood, the stories that we can gather from published material, police reports, and oral interviews reveal the networks that existed even when homosexuality was deemed illegal.

[1] Tim Edensor, ‘The Gloomy City,’ in Urban Studies, Vol. 52, 3, February 2015, pp. 422-438, p. 427

[2] Matt Houlbrook, Queer London: Perils and Pleasure in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918-1957, (Chicago, University of Chicago Press).

[3] Emma Vickers, ‘Queer Sex in the Metropolis?,’ in Feminist Review, Vol. 96, 2010, pp. 58-73, p. 67

[4] Vickers, p.66