Are we in an Age of Conspiracy?

By Lucy Ward, 2nd Year History and Spanish

Recent years have seemingly seen a surge in the prevalence of conspiracy theories, misinformation and fake news. In the age of the internet and the rapid spread of information that comes with it, one can be forgiven for thinking that conspiracy theories are a modern phenomenon; certainly, social media platforms are the ideal breeding ground for misinformation and its dissemination. In reality, however, conspiracy theories have a longstanding presence throughout history, and their origins and uses are largely similar to the conspiracies of today.

The earliest known usage of the term ‘conspiracy theory’ appeared in a letter written by Charles Astor Bristed to the editor of The New York Times on 11 January 1863, in which he claimed that British aristocrats were intentionally interfering in the American Civil War in order to advance their own financial interests. Although this was the first time the term was used, the idea that malevolent and powerful groups or organisations are secretly responsible for certain events can be seen throughout history.

Take, for example, the mid fourteenth century, when, following the first outbreak of the Black Death, widespread rumours accused the Jewish population of causing the disease by poisoning wells. Due to a lack of medical knowledge in medieval times, many turned to religiously motivated explanations for the pandemic, one popular example being that the Jewish people were working with the devil to destroy Christianity.

Here, we can see the widely accepted psychological explanation for conspiracy theories. It explains them as a response to fear and uncertainty, particularly after a shocking or traumatic event such as a war, a terrorist attack, or a pandemic, and with a tendency to build upon beliefs or prejudices already held by individuals.

Perhaps the clearest example of this explanation is 9/11. In the aftermath of this deeply traumatic event, which shook the United States and the wider world to its core, conspiracy theories emerged. They suggested that the American government had prior knowledge of the attacks and had failed to stop them, or that they had even been involved in planning the attacks themselves. These conspiracies indicate two things: first, that the American people were so shaken by the attacks that they scrambled to make sense of them by finding someone to blame; and second, that there were pre-existing notions that the United States government was untrustworthy and working against the American people.

Although there have been occasions on which these suspicions have been proved correct, such as the Watergate scandal and the Iran-Contra affair, these theories usually lack concrete evidence and are enforced by circular reasoning. Within such reasoning, both the existence and absence of evidence for a theory are taken as proof of the conspiracy’s existence.

Conspiracies can also arise from situations deemed unusual or perplexing. When Edward IV chose to marry Elizabeth Woodville in 1464, rather than pursuing a politically advantageous marriage to a foreign princess, a conspiracy arose that her mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, had used witchcraft to entice the king to marry her daughter. This can be understood as a way of trying to make sense of a marriage to a relatively low-born widow, which was deemed by many at the time as largely unthinkable or even deeply wrong. Similar conspiracies became prevalent in the 15th century, when aristocratic women were accused of using sorcery to their advantage, and this in turn, was followed by the scores of witch hunts which took place in the early modern period.

Crucially, the experience of Elizabeth Woodville and her mother can also be seen as an attempt to discredit her and her unpopular relatives. This highlights another important aspect of conspiracy theories throughout history – their potential for political gain.

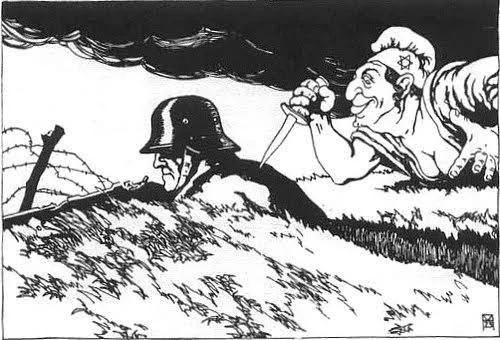

An antisemitic cartoon of the ‘stab in the back’ myth (1919)

One of the most longstanding conspiracies in history is the international Jewish conspiracy, an antisemitic claim that a global Jewish circle is secretly working towards world domination. This theory stretches back as early as the fourteenth century, when rumours circulated during the Black Death, but was popularised during the late nineteenth century after the publication of the antisemitic text The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. This conspiracy theory was capitalised on and further disseminated by Adolf Hitler in the aftermath of the First World War, most notably through the propagation of the ‘stab in the back’ myth which blamed the loss of the war on the Jewish population. The promotion of this conspiracy exploited the fears and uncertainties of the German people and ultimately formed the backbone of the Nazi propaganda machine which propelled Hitler to power in 1933.

More recently, the spread of misinformation and conspiracy has also had dire political consequences. Following false claims made by Donald Trump suggesting the election had been ‘stolen’, an estimated 2000 people stormed the Capitol building in Washington on 6 January 2021, in order to prevent the counting of the electoral college votes. In the lead up to the attack, Trump continually spread false allegations of election fraud, claiming the election had been rigged against him.

Trump also regularly supported claims from the conspiracy group QAnon, including a theory which emerged in 2017, claiming that Donald Trump was leading the fight against a satanic deep-state group engaged in child-sex trafficking and cannibalism. Trump posted numerous times about this theory, first on Twitter, and then, after he was banned from the site, on his social media platform Truth Social. Many of those involved in the Capitol riots were followers of this theory.

A US Capitol rioter, Jacob Chansley (photo credit: PBS News)

The US Capitol riots are a clear example that, although we may not be living in an ‘age of conspiracy’ any more than we were centuries ago, the ease with which these conspiracies are spread and utilised has rapidly expanded. The rise of the internet and mass media has uplifted and popularised many theories, giving a platform to numerous groups or conspiracies which had previously been on the fringes of society. In an age of fake news and misinformation, it is crucial to understand why these conspiracies appear, how they gain popularity, and the ways in which they have been used in history.

Edited by Scarlett Bantin