The Legacy of Beatrix Potter: artist, naturalist and conservationist

By Lotte Hutton, Third Year Zoologist

Though best known for her children’s books, Beatrix Potter dedicated her life to the conservation of the natural world. This Women’s History Month, the Bristorian celebrates her lesser-known achievements in conserving one of the most remarkable natural landscapes in England.

Last September, I arrived at an especially drenched Hilltop Farm on a stormy afternoon and wandered the gardens, now filled with the dead heads of once-blooming flowers. The stone path was slippery and uneven but led to a house I had dreamt of visiting when I was a Beatrix Potter-obsessed 10-year-old. Although a largely unassuming building, I was immediately starstruck by its status as the former residence of Beatrix Potter.

Now owned by the National Trust, Hilltop Farm is a simple stone cottage in pristine condition, left almost untouched since Beatrix Potter herself was walking the corridors. Though not her permanent residence, Beatrix filled it with her collection of treasures such as drawings and trinkets, bringing to life the dark rooms and pokey corridors. These objects were in equal parts memorabilia of her career and natural history artefacts.

Though hugely famous as an author, Beatrix Potter was a passionate naturalist, producing beautiful paintings of plants, fungi, insects and animals as studies. In 1892, she befriended a man named Charlie McIntosh while on holiday with her family. McIntosh was a postman and self-educated naturalist, who observed the flora and fauna of his postal delivery routes and encouraged Beatrix to go further with her drawings, increasing their scientific precision. He helped her study nomenclature, scientific classification, and microscope techniques. Following her personal pursuit of the study of mycology, Beatrix submitted a research paper to the Linnean Society of London in 1897. This paper expanded on her drawings of fungus spores and her theory of their germination; it was accepted, but she was prevented from attending the reading of her paper because she was a woman.

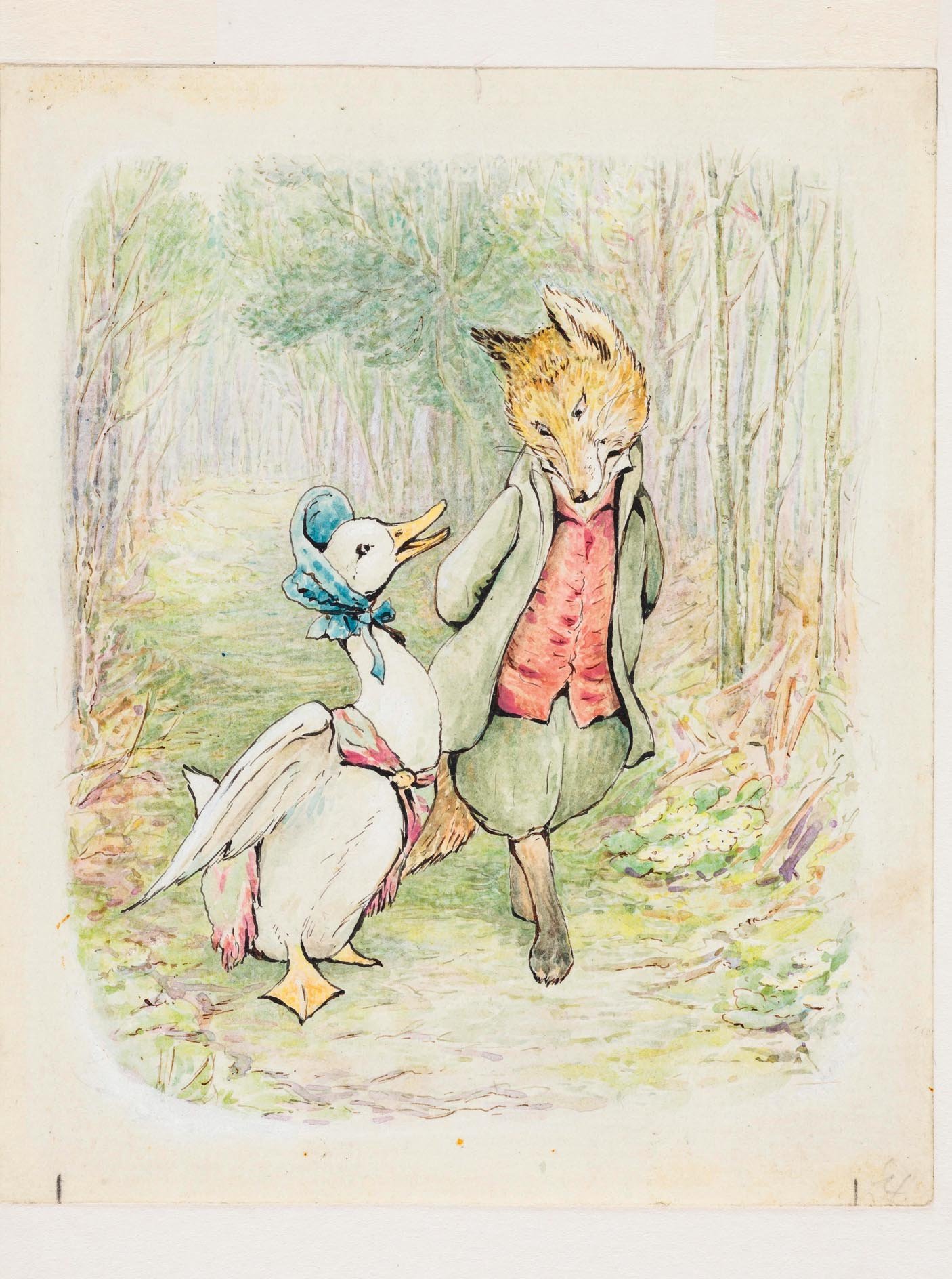

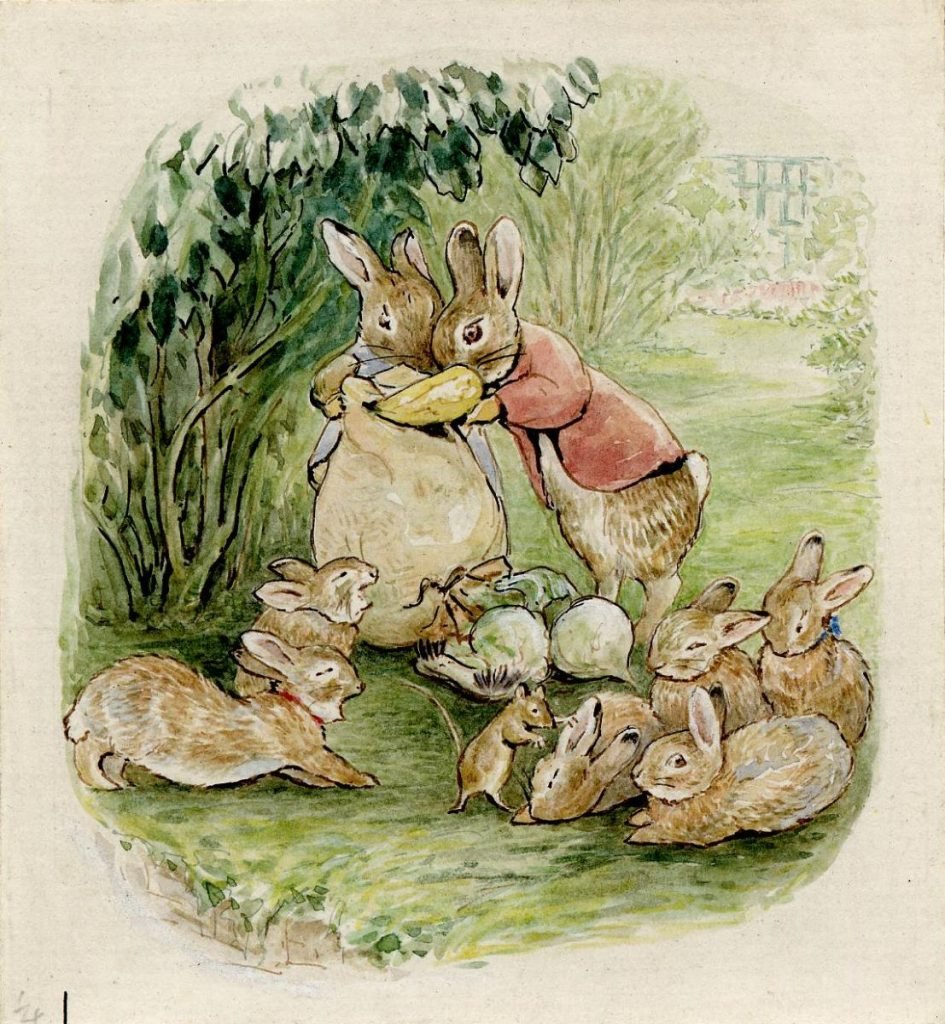

Beatrix’s eye for detail and scientific mind combined to give her a deep and knowledgeable understanding of the natural world. To many, the name Beatrix Potter is synonymous with the adventures of her watercolour woodland creatures, but a broader look at her work shows her artistic talents extended far beyond hedgehogs in petticoats. Luckily, hedgehogs in petticoats are enormous money makers, and her imagination flourished once she used her fortune to leave the claustrophobia of Victorian city life.

In 1905, Beatrix relocated to the Lakes where the majority of her childhood summers had been spent. Armed with an enormous, fictional rabbit fuelled budget and a lifelong love of the Lake District’s landscape, she bought Hilltop Farm and threw herself into the world of Cumbrian farming life. In the early 20th century, the lakes became at risk of extensive property development and industrialisation. Lake Windermere, the largest lake in England, was threatened with extensive development along its shoreline. Outraged by this, Beatrix sold 50 redrawn Peter Rabbit illustrations through a magazine in Boston to raise funds for conservation efforts.

As both a fierce campaigner for local conservation and a sharp businesswoman, Beatrix worked to buy up as much of the surrounding land as she could. By the end of her life she owned 4000 acres of land including 15 farms. She ensured that the many tenant farmers she employed were those that would care for and farm the land using traditional Cumbrian practices that otherwise could have been lost to time. She was even elected president of the Herwick Sheep Breeders’ Association in 1943, sadly she did not live to take the role.

Her land and the farms within it were left to the National Trust upon her death in December 1943. Without her acquisition and donation of these acres of beautiful countryside, the Lake District might be an entirely different landscape today. As the UK loses more and more of its wild spaces, the conservation of iconic landscapes is more important than ever. Luckily, Beatrix Potter was ahead of the game.