From Absurdity to Austerity: Samuel Beckett and the Future of Theatre

By Alice Peters, 3rd Year History

Samuel Beckett was an Irish playwright, poet, and novelist, born in 1906 in Dublin, Ireland. Beckett spent his early career travelling throughout Europe before settling in Paris in 1937 where he would stay during the Second World War, joining the French Resistance until 1942.

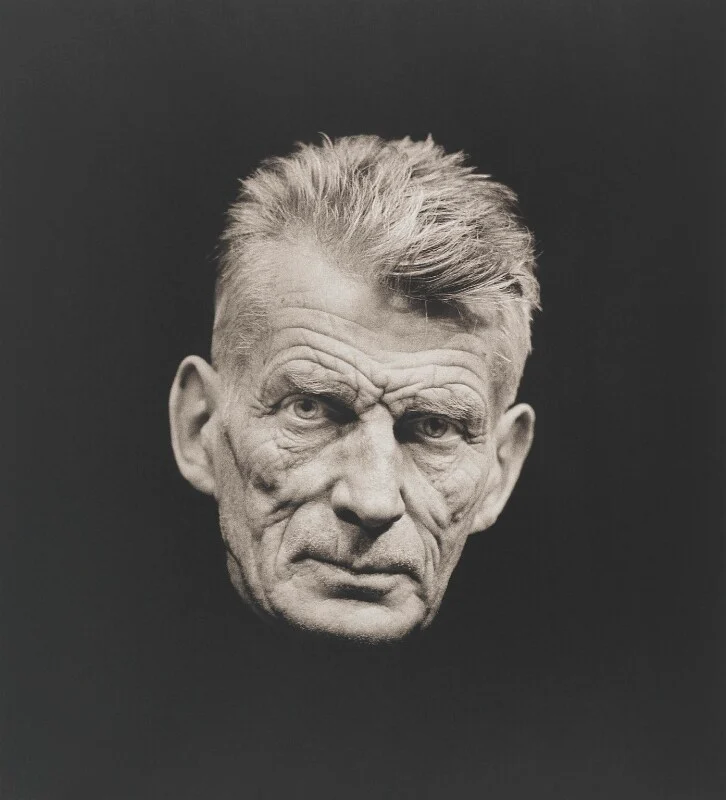

Figure 1: Samuel Beckett. Credit: National Portrait Gallery

Beckett earned critical acclaim for his bleak and comedic commentary on postwar society and human nature, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1969. He was influenced by modernist literature and philosophy, while using novel dramatic techniques to shift the nature of postwar theatre that was grappling with a disillusioned and traumatised audience.

He experimented with non-linear storytelling, abandonment of reality, and existential concepts of life itself. He drew heavy influence from works like Ulysses by James Joyce, or concepts such as the Absurd from Albert Camus.

Beckett transported these techniques to the stage in Waiting for Godot, his 1953 play in which two tramps try to pass time whilst they wait for the unknown figure of Godot. The plot is famously constrained to two repetitive acts and the set consists of a few rocks and a tree. The bareness of both the stage and plot places heavy emphasis on the dialogue. Beckett adopts many styles of dialogue throughout the play. Bouncing between short repetitive phrases like ‘let’s go’ leading them nowhere, or long and unrelenting monologues littered with existential reflection on suffering and salvation. His writing contained both firm silences, as well as conversations written to fill in the gaps. The definition of communication is lost within the characters' meaningless use of language.

The uncertainty and almost awkwardness these techniques facilitate reflects the audiences’ own feelings of displacement following the war and anxiety for the future in Cold War contexts. The Second World War caused over 70 million deaths, including the use of two atomic bombs, and the atrocities of the Holocaust. Almost no one escaped untouched by the damages caused. This trauma shattered long-held beliefs about human morality, religion, and progress reflected by the domination of secularism in the following decades. The public could no longer rely on traditional narratives of order, leaving an atmosphere of lost faith. What is the role of performance, when nothing is certain anyway?

Beckett challenged traditional modes of theatre and adapted to this traumatised audience mirroring other absurdist plays, for example Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano (1950), or Harold Pinter’s The Caretaker (1960), both of which grappled with humanity’s purpose and the frailty of verbal communication in the face of suffering. These playwrights used dark humour, influenced by comic traditions from sources such as mime, double acts, and acrobats. The comedy acted as a form of liberation from the bleak discussions of human nature, using laughter as the audience’s catharsis.

Beckett was able to turn limitation into innovation, powerfully capturing the mood of the audience despite using radical techniques and minimalist devices. At the time his radicalism was not well received by some, and he was facing censorship in the form of Lord Chamberlain demanding removal of some lines due to their ‘vulgarity’ and ‘blasphemy’.

Despite this Waiting for Godot has held a strong and enduring legacy as a modern classic. His legacy is not confined to the Theatre of the Absurd as his influence is found within thorough stage direction, minimalist sets and casts, and experimental films like David Lynch’s Rabbits (2002) which touches on themes of existentialism and waiting.

Modern theatre faces pressures that, while different from Beckett’s postwar audience, requires a similarly adaptive rethinking of form and scale. Modern theatre has entered a period of instability, both economically and culturally. As the Society of London Theatre and UK Theatre has assessed, public investment has fallen by 18% per person since 2010, with local authority support down by up to 48% in some areas. The creative industry not only has an economic significance as it is now worth over £125 billion to the UK economy, but it is also crucial culturally, providing access to a world of arts, fostering empathy and confidence beyond the digital world.

Despite its economic and cultural worth, theatre is facing shrinking budgets and consequently the number of original and ambitious productions has diminished. As Chris Stafford, chief executive of the Leicester Curve, told the BBC, doing ‘more with less’ is now the reality that has reshaped the creative landscape. Minimalism has surged in popularity driven by tighter budgets and an increased hunger for authentic and human performance in an age of artificiality. Echoing Beckett’s own artistic instincts, contemporary theatre is stripping back spectacle, recentring language and human interaction on stage.

If Beckett taught us anything, it’s that even dire conditions can be the rife with artistic potency and meaningful performance in an age of instability.